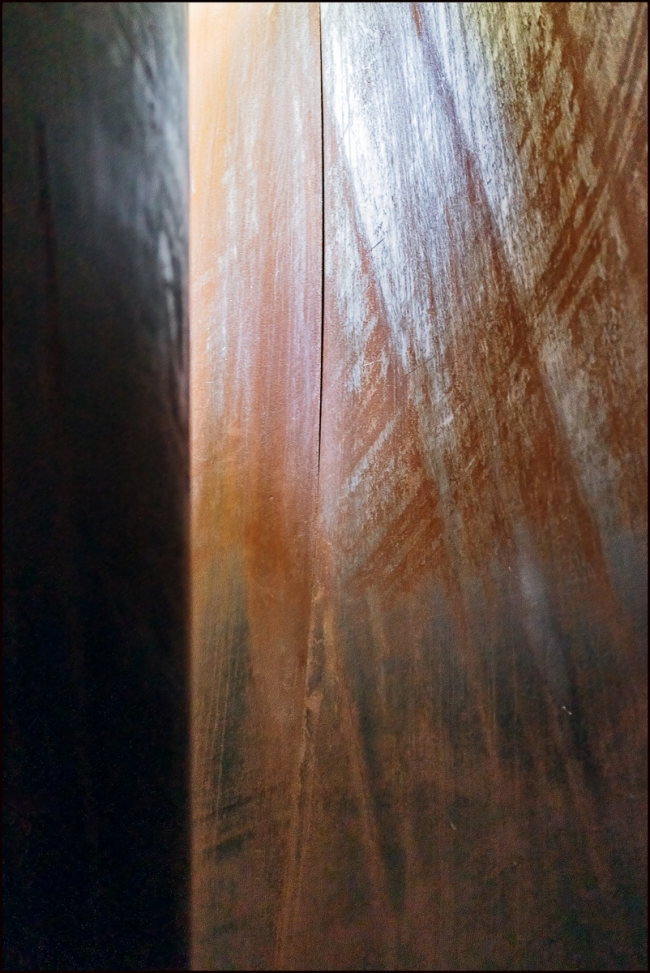

Another exhibit/installation I really liked was that of works of Richard Serra. According to The Guggenheim museum:

Richard Serra was born in 1938 in San Francisco. While working in steel mills to support himself, Serra attended the University of California at Berkeley and Santa Barbara from 1957 to 1961, receiving a BA in English literature. He then studied as a painter at Yale University, New Haven, from 1961 to 1964, completing his BFA and MFA there. While at Yale, Serra worked with Josef Albers on his book The Interaction of Color (1963). During the early 1960s, he came into contact with Philip Guston, Robert Rauschenberg, Ad Reinhardt, and Frank Stella. In 1964 and 1965 Serra received a Yale Traveling Fellowship and traveled to Paris, where he frequently visited the reconstruction of Constantin Brancusi’s studio at the Musée National d’Art Moderne. He spent much of the following year in Florence on a Fulbright grant and traveled throughout southern Europe and northern Africa. The young artist was given his first solo exhibition at Galleria La Salita, Rome, in 1966. Later that year, he moved to New York where his circle of friends included Carl Andre, Walter De Maria, Eva Hesse, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Smithson.

In 1966 Serra made his first sculptures out of nontraditional materials such as fiberglass and rubber. From 1968 to 1970 he executed a series of Splash pieces, in which molten lead was splashed or cast into the junctures between floor and wall. Serra had his first solo exhibition in the United States at the Leo Castelli Warehouse, New York. By 1969 he had begun the Prop pieces, whose parts are not welded together or otherwise attached but are balanced solely by forces of weight and gravity. That year, Serra was included in Nine Young Artists: Theodoron Awards at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. He produced the first of his numerous short films in 1968 and in the early 1970s experimented with video. The Pasadena Art Museum organized a solo exhibition of Serra’s work in 1970, and in the same year he received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship. That year, he helped Smithson execute Spiral Jetty at the Great Salt Lake in Utah; Serra, however, was less intrigued by the vast American landscape than by urban sites, and in 1970 he installed a piece on a dead-end street in the Bronx. He received the Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture in 1975 and traveled to Spain to study Mozarabic architecture in 1982.

Serra was honored with solo exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Tübingen, Germany, in 1978; the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, in 1984; the Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, in 1985; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1986. The 1990s saw further honors for Serra’s work: a retrospective of his drawings at the Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht; the Wilhelm Lehmbruck prize for sculpture in Duisburg in 1991; and the following year, a retrospective at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. In 1993 Serra was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1994 he was awarded the Praemium Imperiale by the Japan Art Association and an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from the California College of the Arts, Oakland. Serra has continued to exhibit in both group and solo shows in such venues as Leo Castelli Gallery and Gagosian Gallery, New York. He continues to produce large-scale steel structures for sites throughout the world, and has become particularly renowned for his monumental arcs, spirals, and ellipses, which engage the viewer in an altered experience of space. From 1997 to 1998 his Torqued Ellipses (1997) were exhibited at and acquired by the Dia Center for the Arts, New York. In 2005 eight major works by Serra were installed permanently at Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and in 2007 the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted a major retrospective of his work. Serra lives outside New York City and in Nova Scotia.

I’ve always been attracted to old, rusting machines and indeed rusting metal of all kinds. I just loved walking around and inside! Yes, some of the sculptures are designed so that you can walk inside and through them. This can lead to some surprise encounters. See next to last picture where this guy started to walk through an opening into a space where I was lining up to take a picture. I don’t know who was more surprised, him or me. At least I managed to keep enough presence of mind to press the shutter release.

For more information see here on the Dia Beacon website.

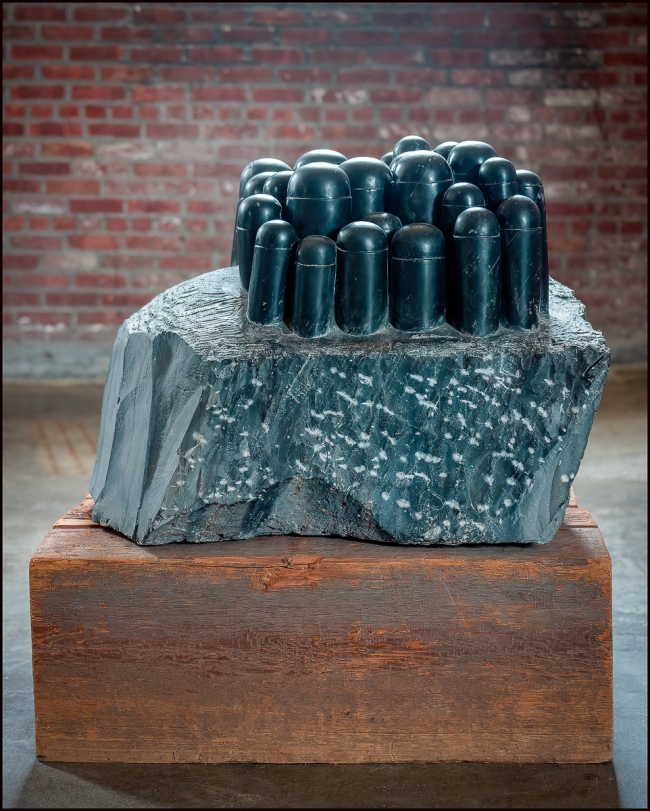

But then I guess you can’t like everything by a particular artist. For example: I don’t particularly like the piece below, also by Serra.

Taken with a Sony A7IV and Samyang 45mm f1.8