If you live in, or near my village (Briarcliff Manor, N) and if you frequent the village Park, Law Park you’ve probably seen the monument above. You may also have read the text on the plaque below.

For those who haven’t, It briefly tells the story of Lt. John Kelvin Koelsch, a son of Briarcliff Manor who died October 16, 1951 in the line of duty at a Prisoner of War Camp in North Korea, during the Korean War. He was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously, August 2, 1955.

But there are actually two stories. The first is Koelsch’s own amazing story of courage and tragedy. You’ll notice that he died in 1951, but the date on the plaque indicates what it was placed only in 2016. That is the second story: How the Village of Briarcliff Manor found out about Lt. Koelsch, established that he had been a Briarcliff resident and caused the monument to be erected.

John Kelvin Koelsch, was born on 22 December 1923 in London, England to a family where the father was an international banker. He came to Briarcliff when he was five and lived there with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Henry A Koelsch, attending the Scarborough School. Travelling with his parents and brothers to England he studied at the Westminster School in London. 1)

Scarborough School, Briarcliff Manor, NY

In 1938, after the death of his father, he returned to Briarcliff where he took up residence with his Godfather, the late George Weeks of Braeview, Central Drive and Mrs. Weeks. He was resident off and on from 1928 to 1938 and from 1938-1945.1)

“Jack” Koelsch entered Princeton after Choate in September 1941. He joined the Navy as a torpedo bomber pilot during World War II, but returned to the University and graduated in 1949 — which was not unusual for members of his war-torn class.

He enlisted as an Aviation Cadet in the U.S. Naval Reserve on 14 September, 1942. He returned to Princeton for instruction under the College Training Program in May 1948 followed by an assignment in February 1949 with the Naval Aircraft Torpedo Unit, Quonset Point, Rhode Island. During the next few years, he served at Naval Air Stations at Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Norfolk, Virginia, and subsequently flew with Composite Squadron 15 and Torpedo Squadrons 97 and 18. He became an accomplished torpedo bomber pilot, and was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) on August 1, 1946. Despite first entering Princeton in September 1941, he returned to the university after the war, and finally graduated in 1949. Following flight training, he was commissioned an ensign in the Naval Reserve on 23 October 1944. After completing flight training, he served in the Pacific War. He was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) 1 August 1946 and transferred to the U.S. Navy two months later on 11 October. 5)

Before he was called up for the Korean War, Koelsch, an English major, planned to go to law school. His sister-in-law, Francita Stuart Koelsch Ulmer, said his optimistic nature can be seen in the title of his thesis, “A Heritage of Hope,” on 19th-century British author George Meredith. “John was the most outstanding brother, a leader, a great athlete, and intellectually stimulating — someone men admired and followed,” says Ulmer.

After the outbreak of the Korean War, he joined Helicopter Squadron 1 (HU-1) at Miramar, California, in August 1950. As Officer in Charge of HU-1, Detachment 8, he joined USS Princeton (CV-37) in October for pilot rescue duty off the eastern coast of Korea. He served in Princeton until June 1951, when he joined Helicopter Squadron 2 (HU-2) for pilot rescue duty off Wonsan, Korea, then under naval blockade. He provided lifeguard duty for pilots who were downed either in coastal waters or over enemy-held territory. 5)

Helicopter similar to the one flown by Lt. Koelsch

USS Princeton (CV-37) underway in 1965

On 22 June, Koelsch and ADAN George M. Neal, his crewman, rescued Ens. Marvin D. Nelson, Jr., of Composite Squadron (VC) 3 from the waters of Wonsan Harbor, southeast of Yo-Do Island, after Nelson had bailed out of his crippled Vought F4U Corsair.

Late on the afternoon of 3 July 1951, Koelsch and then-AD3 Neal volunteered to fly deep into North Korea to rescue Capt. James V. Wilkins, USMC, who had bailed out of his burning Corsair after it had been hit by enemy fire during an armed reconnaissance mission about thirty-five miles southwest of Wonsan. Despite approaching darkness, worsening weather, and enemy ground fire, Lt. (j.g.) Koelsch located the downed pilot in the Anbyon Valley and began maneuvering to pick him up. Thick fog prevented the covering aircraft from protecting the unarmed helicopter, and intense enemy fire downed it as AD3 Neal was in the process of hoisting the injured man up. Koelsch, Wilkins and Neal evaded the enemy for nine days, only to be taken captive by North Korean forces before they could reach safety.

During his imprisonment, Koelsch steadfastly refused to submit to his captors in any manner although brutally beaten and abused; his fortitude and personal bravery inspired his fellow prisoners. He died of malnutrition and dysentery in a Communist prison camp on 16 October 1951. For his conspicuous gallantry, intrepidity, and heroic spirit of self-sacrifice, Lt. (j.g.) Koelsch was awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously, on 3 August 1955.. 2)

His remains were subsequently returned to the United States where they were buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. His grave can be found in section 30, grave 1123-RH.

Koelsch’s grave in Arlington Cemetery.

In 1955 Koelsch was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Eisenhower, the first helicopter pilot so honored. (AD3 Neal later received the Navy Cross). The citation notes his courage in combat and his bravery, fortitude, and consideration for his companions as a POW.

Navy Medal of Honor.

A Navy helicopter squadron assigned to Marine Corps Base Hawaii named their flight simulator building for Koelsch. Lt. Cmdr. Ike Stutts wrote: Because Koelsch was “a Navy helicopter pilot who rescued a Marine aviator, we thought there could be no better fit for the name of our building.” 2). A Navy destroyer escort was also named after him. The Korean War Memorial in Lasdon Park and Arboretum, in Katonah devotes an entire face to him.

USS Koelsch

Lasdon Korean War Memorial. Right face devoted to Lt.Koelsch

Perhaps most importantly his sacrifice and those of others led to the establishing of The Code of the United States Fighting Force on 17 August 1955. This code of conduct is an ethics guide and a United States Department of Defense directive consisting of six articles to members of the United States Armed Forces, addressing how they should act in combat when they must evade capture, resist while a prisoner or escape from the enemy. 4)

So why was there no monument to Koelsch in Briarcliff Manor until 2016?

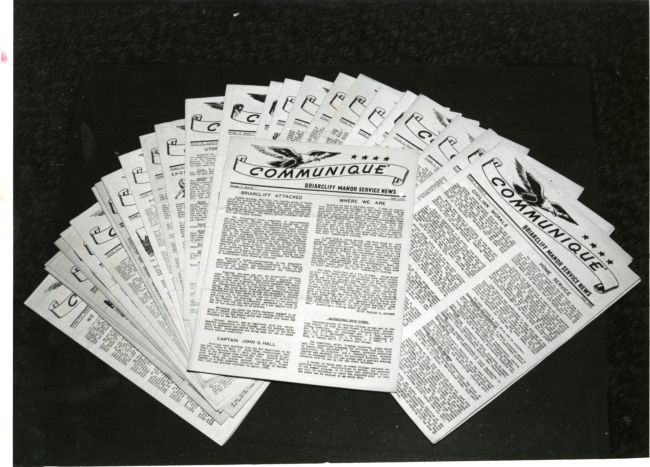

Communique

During WWII Briarcliff Manor produced a series of newsletters entitled “Communique”. The series ran from December 1942- September 1945. The reason for its creation was given in the very first issue:

“Communique has been created by the people of Briarcliff Manor to provide their boys and girls who are serving in our nation’s armed forces news of the village that will be of interest or amusement and to provide an exchange for news between Manorites in the service.”

The BMSHS had acquired a set. Current BMSHS Executive Director, Karen Smith was organizing them and, in doing so had come across the name John Kelvin Koelsch and noted his connection to Briarcliff Manor. Later, she came across his story, looked for his name on the War Memorial in Law Park and noticed that it wasn’t there. She subsequently wrote (in an email dated Jul 10, 2013):

“…I checked out John Kelvin Koelsch online. Phil Reisman of the Journal News wrote a column on March 28, 2011 ‘Korean War Flier’s sacrifice finally gets its local due.’

The article reports information that is available on a couple of other sites, including Koelsch’s Congressional Medal of Honor citation.

But he also wrote as his concluding paragraph, ‘ My original column from 2009 reported that despite his heroism, Koelsch’s name could not be found at either the Korean War Memorial at the county-owned Lasdon Park in Somers or at the memorial outside Mount Pleasant Town Hall that includes all of New York’s Medal of Honor recipients going back to World War I’.

And as you can see, his name is missing from the Briarcliff Manor War Memorial (I just took the picture this morning).

Obviously something has to be done about this…we need to correct the historical record” 6)

It seems that this situation had occurred because Lt. Koelsch had enlisted in California and so the connection to Briarcliff Manor had been missed. However, after some research his long-time residency in Briarcliff Manor was confirmed.

“While he was at boarding school/college from ’38-’42 and then in the Navy, his legal residence was Scarborough. Upon his commissioning in November ’45 he was listed as a resident of Scarborough. His mother inherited property in LA and moved there in ’46 or ’47. Evidently, she regularly returned to the area from LA and always considered Scarborough as her home – according to a still-living sister-in-law. While Koelsch was still in the Navy doing research (’45-’48) he did switch his legal residence to LA circa ’47. He reentered Princeton in May ’48 and graduated in February ’49.” 3)

After that various actors e.g. the BMSHS; the Village authorities; the American Legion; concerned T etc.) were involved in an effort to ensure that Lt. Koelsch’s sacrifice was suitably recognized in the village. In 2016, this resulted in the installation of the memorial in Law Park. Although our village has named many roads for soldiers who have served/died in war, we have yet to see a road named in honor of Lt. Koelsch. This should be our next goal.

The full text of his Medal of Honor Citation reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving with a Navy helicopter rescue unit. Although darkness was rapidly approaching when information was received that a marine aviator had been shot down and was trapped by the enemy in mountainous terrain deep in hostile territory, Lt. (j.g.) Koelsch voluntarily flew a helicopter to the reported position of the downed airman in an attempt to effect a rescue. With an almost solid overcast concealing everything below the mountain peaks, he descended in his unarmed and vulnerable aircraft without the accompanying fighter escort to an extremely low altitude beneath the cloud level and began a systematic search. Despite the increasingly intense enemy fire, which struck his helicopter on one occasion, he persisted in his mission until he succeeded in locating the downed pilot, who was suffering from serious burns on the arms and legs. While the victim was being hoisted into the aircraft, it was struck again by an accurate burst of hostile fire and crashed on the side of the mountain. Quickly extricating his crewmen and the aviator from the wreckage, Lt. (j.g.) Koelsch led them from the vicinity in an effort to escape from hostile troops, evading the enemy forces for nine days and rendering such medical attention as possible to his severely burned companion until all were captured. Up to the time of his death while still a captive of the enemy, Lt. (j.g.) Koelsch steadfastly refused to aid his captors in any manner and served to inspire his fellow prisoners by his fortitude and consideration for others. His great personal valor and heroic spirit of self-sacrifice throughout sustain and enhance the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.”

Sources:

- “Medal of Honor Posthumously Given to Briarcliff Flyer”. The Citizen Register, Ossining, Tuesday August 9, 1955

Naval History and Heritage Command

- Email from Barry Bosac, May 28, 2015

- Code of the United States Fighting Force

- Princeton Alumni Weekly. The Medal of Honor by By Michael Goldstein ’78, Featured in the November 3, 2010 Issue

- Karen Smith email dated Jul 10, 2013

- Files at the Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society, available for consultation at the Eileen O’Conner Weber Historical Center, 1 Library Road, Briarcliff Manor, NY (on the lower level of the library building).

Further Reading:

For an interesting, and colorful take on the Koelsch story see: The Badass Story of the First Helicopter Pilot to Receive the Medal of Honor, by Karl Smallwood, in Today I Found Out, November 18, 2018.