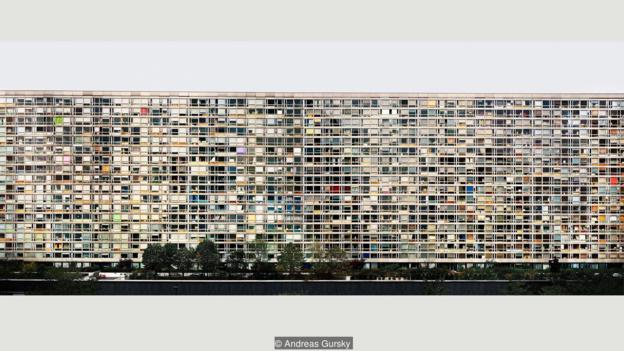

Andreas Gursky’s photograph of a Montparnasse tower block is a stunning mosaic of colour (Credit: Andreas Gursky)

I just came across this article (The stunning photographs that are like paintings) on the BBC website. It deals ith the so-called “Dusseldorf School” and refers to an exhibition featuring their work at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. In particular it draws attention to the influence of Bernd and Hilla Becher on the photographers (Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Struth, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff, Jörg Sasse) belonging to the school.

At the heart of Engler’s exhibition is the following question: how important, as an influence upon this special generation, were their teachers in Düsseldorf, the German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher? The answer, it transpires, is: extremely important. If you aren’t already familiar with the Bechers, then it’s time to become acquainted with two crucial figures in the history of photography.

Draconian and dispassionate.It was 1976 when Bernd Becher (1931-2007), who had trained as a painter, was appointed professor of photography at the Academy of Art in Düsseldorf. His wife and artistic partner, Hilla (1934-2015), was never given a formal role at the institution, but she always worked closely with her husband, who often taught at home, and was an equally important influence upon his students until 1996, when Bernd left the faculty.

They had met as students, themselves, at Düsseldorf’s Kunstakademie in 1957, and began collaborating two years later, before getting married in 1961. During the 60s, they spent time in New York City, where they encountered avant-garde art, and mixed with Conceptual and Minimalist artists such as Carl Andre. “Their experience in New York totally changed the way they perceived photography,” Engler says.

A while back I went to an exhibition of Bernd and Hilla Becher at Dia, a nearby art museum. It featured a number of photographs of industrial buildings and structures and I quite liked them.

At first I didn’t much care much for the work of the other photographers, but it’s now starting to grow on me. I suspect that you really have to see the photographs in person to really “get” them. As the BBC article notes:

As an exhibition featuring their work at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt recently made plain, before the emergence of Gursky and his contemporaries, including Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth, photography was typically seen as something small-scale and black-and-white. Its status as contemporary “art”, i.e. as work that could stand shoulder to shoulder with painting in museums and auction houses, was still a matter of debate.

During the 90s, though, curators and collectors started going wild for the sort of photography that Gursky and his peers were producing: massive, scintillating compositions, like Paris, Montparnasse, printed in full colour, and often presented, in the manner of serious paintings, in heavy wooden frames.

Just looking at tiny pictures on a computer/iphone/ipad just won’t do. Unfortunately, I’ve yet to find an opportunity to see them in their full glory.