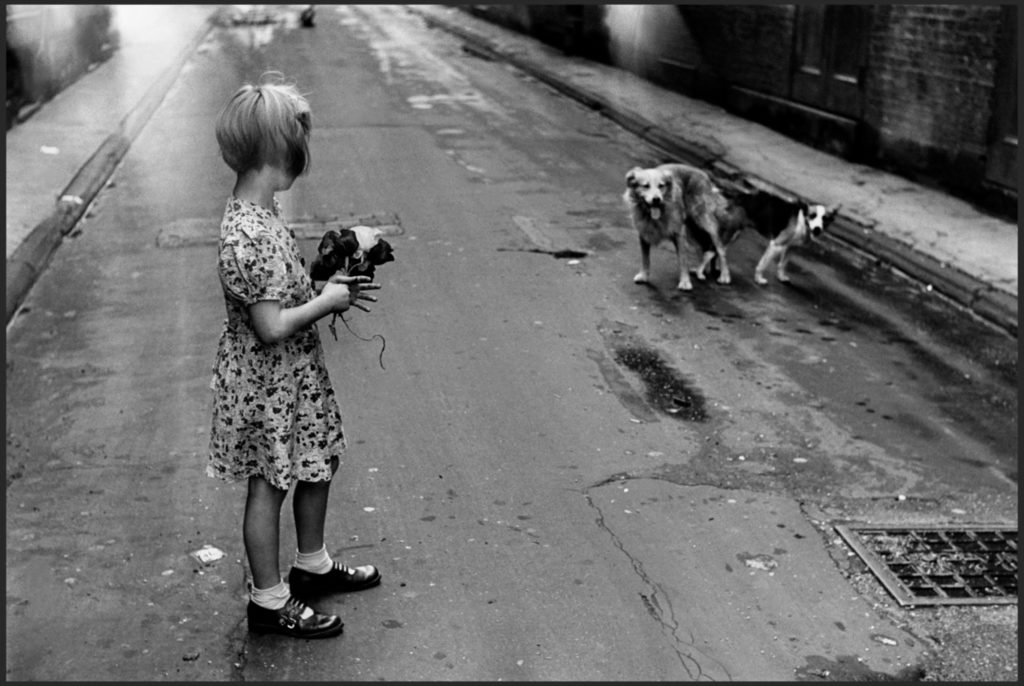

TWO EXHIBITONS BY JOEL MEYEROWITZ

BETWEEN THE DOG AND THE WOLF and MORANDI, CÉZANNE AND ME

HOWARD GREENBERG GALLERY

September 7 – October 21, 2017

NEW YORK – Two exhibitions of photographs by Joel Meyerowitz will be on view at Howard Greenberg Gallery from September 7 to October 21, 2017. Between the Dog and the Wolf presents images from the 1970s and 80s made in those mysterious moments around dusk. Many of the works will be on display for the first time. Morandi, Cézanne and Me surveys Meyerowitz’s recent still lifes of objects from Paul Cézanne’s studio in Aix-en-Provence and Giorgio Morandi’s in Bologna. The exhibitions will open with a reception on September 7, from 6 to 8 p.m.

Two new books of photographs by Meyerowitz are to be published: Joel Meyerowitz: Cézanne’s Objects (Damiani, October 2017) and Joel Meyerowitz: Where I Find Myself: A Lifetime Retrospective (Laurence King, January 2018).

The exhibition title Between the Dog and the Wolf is a translation of a common French expression “Entre chien et loup,” which refers to oncoming twilight. As Meyerowitz notes, “It seemed to me that the French liken the twilight to the notion of the tame and the savage, the known and the unknown, where that special moment of the fading of the light offers us an entrance into the place where our senses might fail us slightly, making us vulnerable to the vagaries of our imagination.”

The majority of the photographs in the exhibition are from a period when Meyerowitz was spending summers on Cape Cod and had just begun working with an 8×10 view camera. “My whole way of seeing was both challenged and refreshed. I found that time became a greater element in my work. The view camera demands longer exposures, and I began looking into the oncoming twilight and seeing things that the small cameras either couldn’t handle or didn’t present in significant enough quality,” Meyerowitz explains. “What seems of more value to me now, 30 years later, is how that devotion to the questions back then taught me to see in a new and simpler way.”

The exhibition features photographs taken concurrently with Meyerowitz’s iconic series Cape Light, widely recognized for his use of color and appreciation of light. A young woman is perched on a wall that overlooks the Cape Cod Bay in a 1984 print, with the last of the daylight fading into a pink haze. A 1977 view of a dark house with one lit window has a sandy front yard with a sagging badminton net, an abandoned tricycle, and a blue doghouse with peeling paint. In a nearly abstract image from 1984, the viewer can barely see lights from a house on the beach as night falls. Other locations show a view of a serene sky with St. Louis’ Gateway Arch from 1977 and a palm tree in fading blue light in Florida from 1979.

As Meyerowitz notes, “I am grateful that my experience has allowed me to work both as a street photographer and as a view-camera photographer, and that I’m comfortable with both vocabularies. I speak two languages, classical and jazz. Street photography is jazz. The view camera, being so much slower, is more classical, more meditative, it has a different way of showing its content. You can be a jazz musician and play classically, and you can be a classical musician and love the immediacy and improvisation of jazz.”

Morandi, Cézanne and Me reflects Meyerowitz’s fascination with everyday objects, which also served as inspiration to Paul Cézanne and Giorgio Morandi. He was granted permission to photograph in both artists’ studios in 2013 and 2015.

Meyerowitz was struck by the grey walls in Cézanne’s studio, and how every object in the studio seemed to be absorbed into the grey of the background. He photographed just about every object there – from vases, pitchers, and carafes to a skull and Cézanne’s hat. This project spurred him to visit Morandi’s studio to observe the objects that the master still life painter had used as inspiration for over 60 years. Meyerowitz was allowed access to all 275 of Morandi’s famous objects at his home and studio. He worked near the same window, sitting at Morandi’s table, photographing shells, pigment-filled bottles, funnels, watering cans, and other dusty aged objects against the same paper that Morandi had left on the wall, now brittle and yellow with age. Meyerowitz also began to look anew at items he found in Italian flea markets – a dented brass tube, a rusted tin flask, a capped container — and he photographed them placed in grey corners and against heavy canvas backdrops in his studio in Tuscany.

Says Meyerowitz, “My underlying motive – while, of course doing this for my own pleasure – was to provide a catalogue of the objects these painters used in the course of their lives, and show to scholars and other interested viewers, the actual, and for the most part humble, cast-offs and basic forms that these great painters drew their inspiration from.”

About Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz (born 1938) is an award-winning photographer whose work has appeared in over 350 exhibitions in museums and galleries throughout the world. After a chance encounter with Robert Frank, the New York native began photographing street scenes in color in 1962, and by the mid-1960s became an early advocate of color photography and was instrumental in the legitimization and growing acceptance of color film. His first book, Cape Light (1979) is considered a classic work of color photography and has sold more than 100,000 copies. He has authored 17 other books, including Legacy: The Preservation of Wilderness in New York City Parks (Aperture, 2009). As the only photographer given official access to Ground Zero in the wake of September 11th, he created the World Trade Center Archive, selections of which have toured around the world. Meyerowitz is a two-time Guggenheim fellow and a recipient of awards from both the NEA and NEH. He is a recent winner of the Royal Photographic Society’s Centenary Award, its highest honor. For his 50 years of work in 2012, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Lucie Awards, an annual event honoring the greatest achievements in photography. This January, Meyerowitz was inducted into the Leica Hall of Fame for his contribution to the photographic genre. His work is held in the collections of many museums, including The Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Museum of Fine Art, Boston. Meyerowitz lives and works in Tuscany and New York City.