I just got my hands on a copy of this marvelous book. I won’t go into detail because there are many excellent reviews available online including:

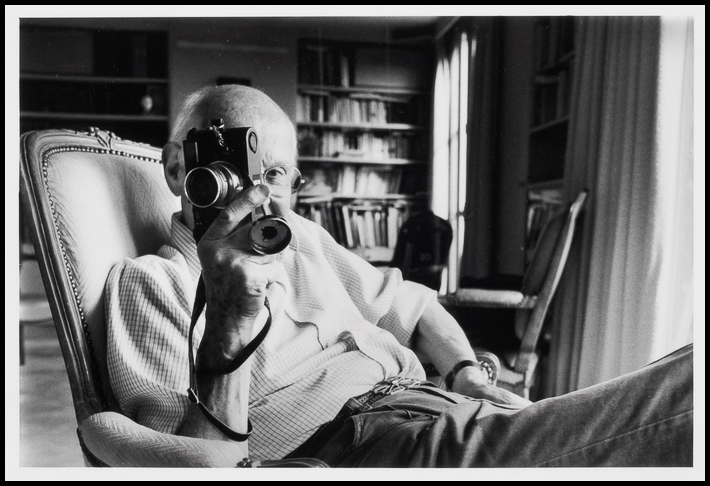

It”s a large and heavy book that I found I either had to place on a table, or even better on a book stand. I found the quality of the reproductions to be excellent. I believe that Mr. Meyerowitz was heavily involved in the production of the book and the selection of images.

The choice of starting with the most recent work first and then working backwards (rather than the more usual starting with the oldest and working forward) was interesting, but after going through the book I found that I wanted to start at the end (i.e. with the oldest work) and read backwards towards the beginning. I found that this helped my understand how his work had evolved over time.

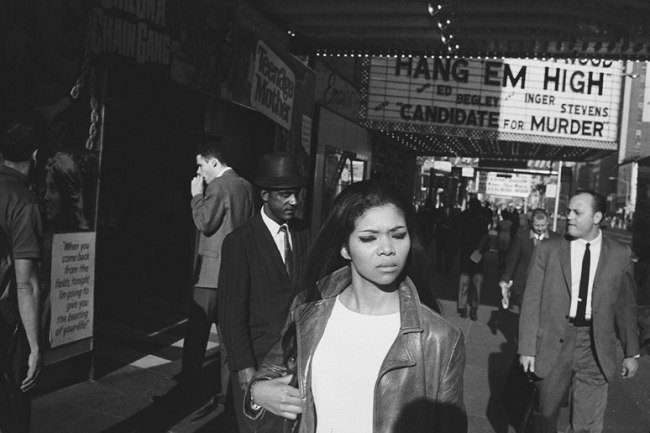

An evolved it certainly has. I find this one of the most impressive things about Mr. Meyerowitz: the way he has frequently re-invented himself. Many photographers find their niche and then stick with it for the rest of their careers. Not Mr. Meyerowitz. He started off in black and white and then became an early advocate of color. He began as a street photographer, but then moved into other genres including landscapes, portraits, still life. He started out using a 35mm camera, but later espoused large format. His reasoning for these changes is nicely explained in the book.

I was particularly impressed with his most recent work: a series of still life photographs. I’ve always liked still lifes, but have taken surprisingly few. The book has inspired me to try to do more.

There’s also an interesting Interview with Joel Meyerowitz: Where I find myself on Lenscratch.

A great book. I thoroughly enjoyed it!