In the previous post I mentioned that we took a look at the Stone Barns Center for Food & Agriculture. According to Wikipedia:

Stone Barns Center for Food & Agriculture is a non-profit farm, education and research center located in Pocantico Hills, New York. The center was created on 80 acres (320,000 m2) formerly belonging to the Rockefeller estate. Stone Barns promotes sustainable agriculture, local food, and community-supported agriculture. Stone Barns is a four-season operation.

Stone Barns Center is also home to the Barber family’s Blue Hill at Stone Barns, a restaurant that serves contemporary cuisine using local ingredients, with an emphasis on produce from the center’s farm. Blue Hill staff also participate in the center’s education programs.

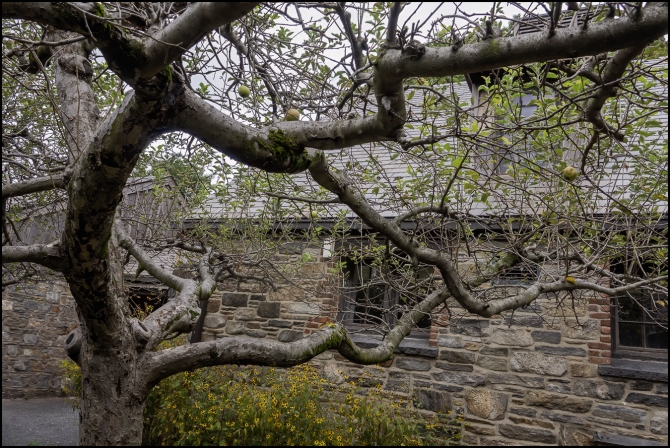

Stone Barns’ property was once part of Pocantico, the Rockefeller estate. The Norman-style stone barns were commissioned by John D. Rockefeller Jr. to be a dairy farm in the 1930s. The complex fell into disuse during the 1950s and was mainly used for storage. In the 1970s, agricultural activity resumed when David Rockefeller’s wife Margaret “Peggy” McGrath began a successful cattle breeding operation.

Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture was created by David Rockefeller, his daughter Peggy Dulany, and their associate James Ford as a memorial for Margaret Rockefeller, who died in 1996. Stone Barns opened to the public in May 2004.

In 2008, Stone Barns opened its slaughterhouse to slaughter its livestock for plating at Blue Hill. Using their own slaughterhouse also eliminated the long and expensive drives to the closest one.

In 2017, Stone Barns published Letters to a Young Farmer, a compilation of essays and letters about the highs and lows of farming life, including Barbara Kingsolver, Bill McKibben, Michael Pollan, Temple Grandin, Wendell Berry, Rick Bayless, and Marion Nestle.

The farm at Stone Barns is a four-season operation with approximately 6 acres (24,000 m2) used for vegetable production. It uses a seven-year rotation schedule in the field and greenhouse beds. The farm grows 300 varieties of produce year-round, both in the outdoor fields and gardens and in the 22,000-square-foot (2,000 m2) minimally heated greenhouse that capitalizes on each season’s available sunlight. Among the crops suitable for the local soil and climate are rare varieties such as celtuce, Kai-lan, hakurei turnips, New England Eight-Row Flint seed corn, and finale fennel. The farm uses no pesticides, herbicides or chemical additives, although compost is added to the soil for enrichment. The farm has a six-month composting cycle using manure, hay, and food waste scraps.

I’ve been to Stone Barns many times. It’s adjacent to the Rockefeller State Park Preserve, a fantastic place for walking.

Stone Barns also has its own restaurant: Blue Hill at Stone Barns. Blue Hill has two Michelin Stars, and the guide describes it as follows:

The passion of Chef Dan Barber is at the core of everything here, where a meal is a true experience that uniquely knits together his vision of improving our foodways, the grit of utilizing the land to provide sustenance, and luxurious touches like crisped linens and fine crystal.

A procession of dramatically presented, farm-fresh seasonal produce kicks off the meal and may include freshly plucked radishes with browned butter, Hakurei turnips dressed with poppy seeds, and morsels of dried honeypatch squash. While the focus is plant-based, heartier compositions may reveal roasted, retired dairy cow plated with root-to-leaf celeriac. The meal may end celebrating how this operation began; as a dairy, with a tower of milk crumbs, milk jam, panna cotta and ice cream to dress poached quince.

The restaurant also has a green star for gastronomy & sustainability. According to Chef, Bastien Guillochon:

“We work with 64 local farms; 30% of our winter menu purchased in October and November to store, preserve or ferment; day boat fisherman off Long Island represent 80% of our seafood purchases; we work closely with vegetable and grain breeders to develop and champion varieties that have lower inputs and require less energy to produce.”

For more on Blue Hill see here.

I once ate at Blue Hill. But that was many years ago, not long after it opened. It was much less expensive then.

The restaurant’s FAQs contain the following statements:

The menu price is $398 – $448 per guest, exclusive of tax and 22% administrative fee. Most reservations include a walking tour of the property prior to your meal. Bookings with this tour support Stone Barns Center programming and are $448 per guest; bookings without are $398.

Menu price is prepaid during booking, and beverages are charged separately at the time of your reservation.

And

Guests are welcome to bring special bottles of wine that are not represented on our wine list. The policy is limited to one 750ml bottle per two guests for a fee of $150 per bottle.

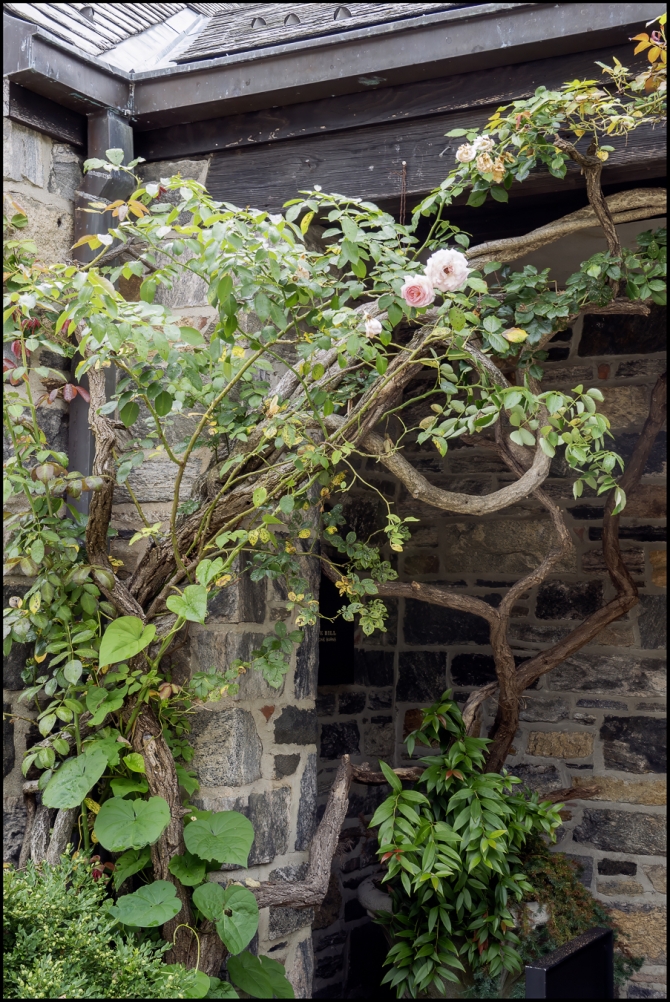

For a few pictures see below. The door to the restaurant was open so I peeped inside. However, I didn’t think it was appropriate to go around taking pictures. From what I saw it looked like a very nice place, as one might expect.

Since it would cost us in excess of $2,000 for dinner for the four of us, we decided we would skip that.

But Blue Hill has another trick up its sleeve: Breakfast:

Blue Hill Cafeteria, our casual, communal space, opened in October of 2021. The Cafeteria is anchored around a large table that opens to the Dooryard Garden, where we offer seasonal outdoor seating amongst the flower beds and their pollinators.

The Cafeteria is open Wednesday through Sunday to guests visiting the Stone Barns Center, highlighting our work with whole grains, preservation and butchery through breakfast, lunch and Community Table by Blue Hill—a family style dinner.

Reservations for both Lunch Tray at Blue Hill Cafeteria and Community Table by Blue Hill can be made online via Tock. All sales are final, and reservations cannot be canceled. If your preferred booking is not available, we encourage you to add your information to the waitlist. New reservations are released one month at a time on the 15th of the month prior.

I don’t recall that we made reservations. But we did get there very early, quite a while before it opened so we were among the first people through the door. We went inside, picked up what we wanted and then went out into the garden to eat. I must say that their offerings were very good, and not ridiculously priced. It was fun sitting in the garden.

After we finished my friends dropped me home, and then set off on their long drive back to Ottawa. It was very nice to see them again.

Taken with a Sony RX10 IV (mostly)