I haven’t shown a lot of interest in Fashion photography. It’s not that I don’t appreciate it – I do, and I have a number of photobooks by/about well known Fashion photographers including Irving Penn, Helmut Newton, Annie Leibovitz and Edward Steichen. I’m also somewhat familiar with the work of others including Cecil Beaton, Richard Avedon, David Bailey, Horst P. Horst, William Klein, David LaChapelle, Lord Snowden, and Mario Testino. It’s just that I don’t think, much as I might like to take pictures of gorgeous women on a beach I don’t think I’ll ever have the opportunity to do so. Moreover, I’m not really comfortable taking pictures of people in general.

However, my interest was piqued when I saw this video on one of my favorite YouTube channels: Alex Kilbee’s: The Photographic Eye – The Photoshoot Which Changed Fashion Photography

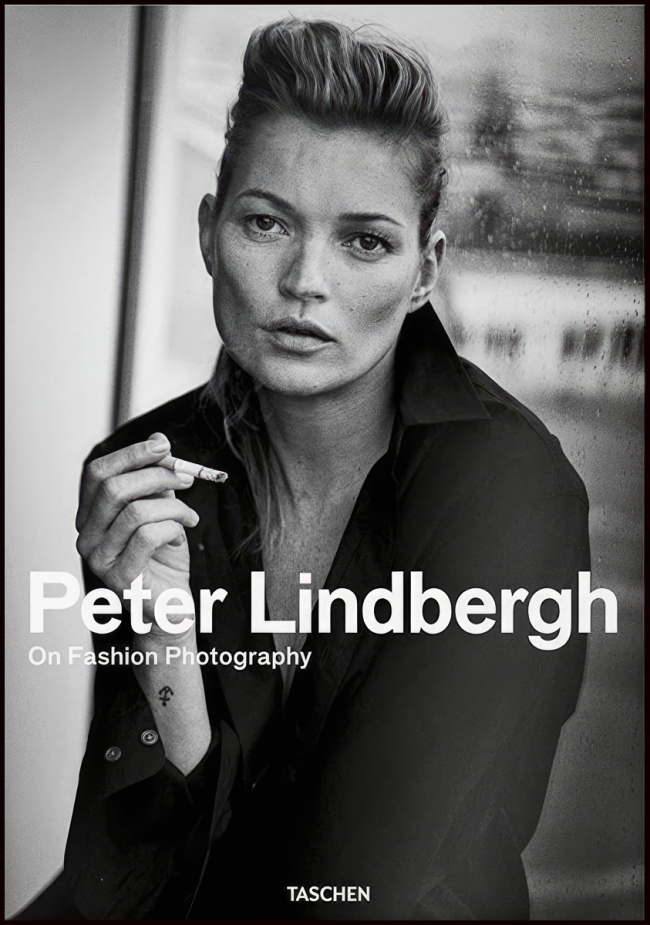

I’d heard of Peter Lindbergh, but had not really appreciated how influential he had been. So I immediately ordered “Peter Lindbergh. On Fashion Photography“, Taschen Books, 2020. In his introduction Lindbergh says:

In 1987, I got a call from Alexander Liberman then the creative director of Condé Nast

I’ve got a couple of books by/about him too. I decided that I would get them after being invited over to the house of, as it turned out, someone who used to work for him). But back to the post:

He couldn’t understand why I didn’t want to work for American Vogue. I told him, “I just can’t take the types of photographs of women that are in your magazine.” I simply felt uninspired by the ways women were being photographed”. He said: “OK, show me what you mean, show me what kind of women you’re talking about.” I wanted a change from a formal, particularly styled, supposedly “perfect” woman – too concerned about social integration and acceptance – to a more outspoken and adventurous woman, in control of her own life and emancipated from masculine control. A woman who could speak for herself.

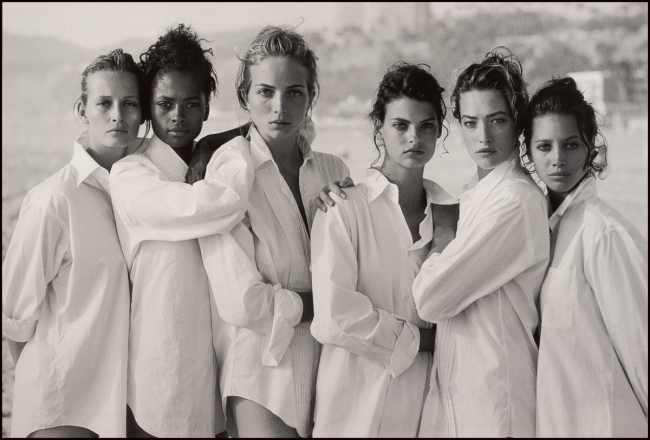

A few months later, following Mr. Liberman’s proposition, I put together a group of young and interesting models and we went to the beach in Santa Monica. I shot very simple images; the models wore hardly any makeup, and I wanted everyone to be dressed the same, in white shirts. This was quite unusual at the time. Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, Tatjana Patitz, and Karen Alexander were all there that day.

Back in New York, Vogue’s editor in chief at the time, Grace Mirabella, refused to print the images. But six months later, Anna Wintour became the the magazine’s editor and discovered the proofs somewhere in a drawer. She put one of them in Condé Nast’s big retrospective book “On the Edge: Images from 100 years of Vogue (1992)”, calling it the most important photograph of the decade. The “supermodel” would go on to represent the powerful woman that I had articulated, and their images dominated fashion visuals for the next 15 years.

The book consists of two distinct parts: a short, but very interesting introduction by Lindbergh himself followed by the heart of the book – Over 300 hundred images (that’s what the book’s sleeve says, but the book actually has 505 pages and the introduction – in English, German, and French – takes up only about 30 of them, and itself contains a number of photographs). Such a large number of images requires some kind of organization and in this case it’s alphabetical by client e.g. Azzedine Alaïa, Heider Ackermann, Giorgio Armani etc.

I like this series of Taschen books. Most photobooks are quite expensive, large format, heavy and difficult to hold. This series is more compact (6×9 inches) and fairly inexpensive. I have a number of them. I guess the only problem with them is that the photographs are relatively speaking rather small, but they’re good enough to provide a thorough overview of his work. Taschen also has a larger format series. I have a few of them too (e.g. Sebastião Salgado‘s wonderful “Genesis” (10×14 inches, but still quite inexpensive for a photobook of this quality), but I find them too big and too heavy to comfortably hold and read.