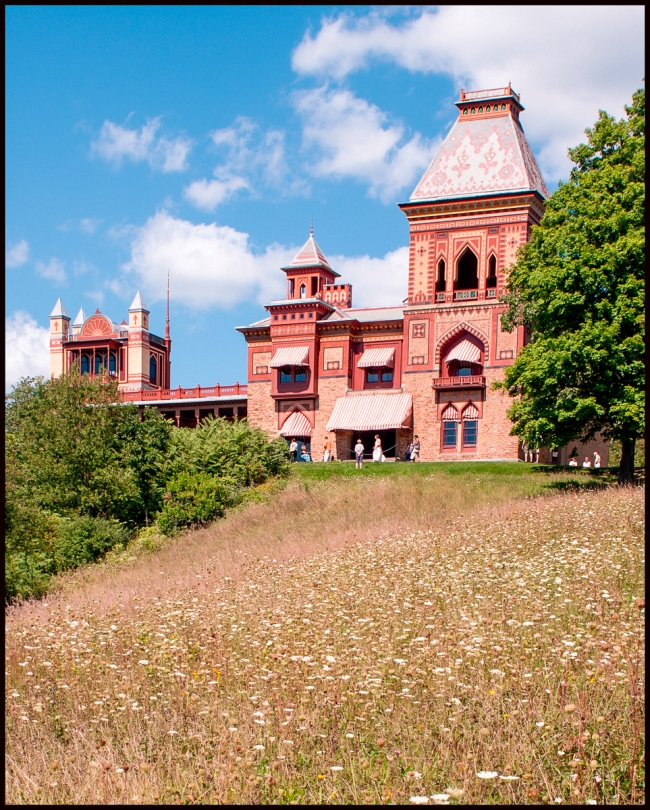

I recently went on a visit to Frederic Church’s Olana, an impressive building perched high above the Hudson River near Hudson New York. I didn’t have the time to walk down to where, in my view, you get the best view of the house. So I used the above picture taken during an earlier visit.

“Frederic Edwin Church was perhaps the best-known representative of the Hudson River School of landscape painting as well as one its most traveled. Born in Hartford in 1826, he was the privileged son of Joseph Church, a jeweler and banker of that city, who interceded with Connecticut scion and collector Daniel Wadsworth to persuade the landscape painter Thomas Cole to accept his son as a pupil. From 1844 to 1846, Church studied with Cole in his Catskill, New York, studio and accompanied him on sketching sojourns in the Catskill Mountains and the Berkshires of Massachusetts. At one point, the master characterized the student as having “the finest eye for drawing in the world.” Following his term with Cole, Church established a studio in New York City and quickly seized a reputation, less for the allegorical landscapes that had distinguished Cole’s output, than for expansive New York and New England views that synthesized sketches of varying locales into vivid compositions. In 1857, however, Church leapt to nationwide and even international prominence with his seven-foot-wide picture Niagara (Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), which stunned spectators in New York and in Great Britain (where it was shown in 1857 and 1858) with its combination of breadth and uncanny verisimilitude.

By the late 1840s, Church had fallen under the spell of the renowned naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, whose treatises and travelogues based on his five-year (1799–1804) expedition in the New World were widely translated and read. In his culminating work, Cosmos (1845), Humboldt implored artists to travel and paint equatorial South America. In 1853, with the young entrepreneur Cyrus Field, Church made the first of two expeditions following Humboldt’s footsteps, chiefly in Colombia; the second, in 1857, in company with the landscape painter Louis Remy Mignot, exclusively in Ecuador. On the large and highly wrought paintings that Church executed based on the sketches from those two journeys, he secured his lasting reputation and became, with Albert Bierstadt, the best known and most successful painter of his generation. The New York exhibition of his ten-foot canvas, The Heart of the Andes (1859; 09.95), housed in an elaborate windowlike frame and illuminated in a darkened room by concealed skylights, was the most popular display of a single artwork in the Civil War era, attracting 12,000 people in three weeks to its New York premiere alone, then traveling to Britain and seven other American cities on a tour lasting two years. The exhibition of The Heart of the Andes in New York was said to have occasioned Church’s courtship and marriage to Isabel Carnes, in 1860, and the couple settled on a hillside farm overlooking the Hudson River at Hudson, New York.

Pursuing Humboldt’s global mandate and responding more particularly to the literature of Arctic exploration, in 1859 Church hired a bark to bear him and the Rev. Louis Legrand Noble, Thomas Cole’s biographer, to the north Atlantic between Labrador and Greenland to sketch icebergs. In 1861, at the outbreak of the Civil War, Church exhibited Icebergs: The North (Dallas Museum of Fine Arts), nearly equal in size to The Heart of the Andes, to now expectant audiences in New York and Great Britain. Subsequent major paintings of tropical and frigid subjects were typically at least seven feet wide and shown as special events in private galleries. Though Church had rarely shared his teacher’s taste for explicit moral and religious allegory in landscape art, he often disclosed both his patriotism and his piety by including pilgrimage crosses in his South American landscapes and brilliant sunsets, auroras, and rainbows overarching the terrain in major works such as Aurora Borealis (1865; Smithsonian American Art Museum) and Rainy Season in the Tropics (1866; Museum of Fine Arts, San Francisco), a pair of pictures that he conceived on the eve of the Union victory in the Civil War.

Church was executing the latter of the two pictures when he and his wife lost their two children to diphtheria a week apart in March 1865. To assuage their grief, they sojourned for several months in Jamaica, where the artist waged the most intense sketching campaign of his professional life, completing some of his most vivid and haunting oil studies of botanical growth and tropical light. In 1867, with the first child of their revived family as well as his mother-in-law, Church and his wife embarked on a pilgrimage of the Old World, primarily in the Holy Land. There they traced Jesus‘ mission through Palestine based on descriptions in the gospels. On his own, the artist also visited the rock city of Petra in Jordan and, later, after the family reached Rome in winter 1869, he sailed across the Adriatic to Athens expressly to admire and sketch the Parthenon. The Metropolitan Museum’s painting, The Parthenon (1871; 15.30.67), was the principal result of that sojourn. Church also produced a spectacular view of Jerusalem (1870; Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City) and the Metropolitan’s The Aegean Sea (1877; 02.23)”.

(Avery, Kevin J. “Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. )

But first we briefly visited Hudson, NY for lunch.

“Hudson is a city and the county seat of Columbia County, New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 5,894. Located on the east side of the Hudson River and 120 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, it was named for the river and its explorer Henry Hudson.

The native Mahican people had occupied this territory for hundreds of years before Dutch colonists began to settle here in the 17th century, calling it “Claverack Landing”. In 1662, some of the Dutch bought this area of land from the Mahican. It was originally part of the Town of Claverack.

In 1783, the area was settled largely by Quaker New England whalers and merchants hailing primarily from the islands of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island, led by Thomas and Seth Jenkins. They capitalized on Hudson being at the head of navigation on the Hudson River and developed it as a busy port. Hudson was chartered as a city in 1785. The self-described “Proprietors” laid out a city grid. By 1786, the city had several fine wharves, warehouses, a spermaceti-works and fifteen hundred residents.

In 1794, John Alsop of the New York City shipping and commission agents, Alsop & Hicks relocated to Hudson for a brief time. He continued to maintain a part interest in the firm and brought in customers from the Hudson area, including: Thomas Jenkins & Sons, Seth Jenkins, and the Paddock family, among others. After Alsop’s death in November 1794, his partner, Isaac Hicks, began to focus more of his efforts towards increasing his sale of whale products-especially oil and spermaceti candles. Hudson grew rapidly as an active port and came within one vote of being named by the state legislature as the capital of New York state, losing to Albany, an historic center of trade from the 17th century.

Hudson grew rapidly, and by 1790 was the 24th-largest city in the United States. In 1820, it had a population of 5,310 and ranked as the fourth-largest city in New York, after New York City, Albany and Brooklyn.[9] Construction of the Erie Canal in 1824 drew development west in the state, stimulating development of cities related to Great Lakes trade, such as Rochester and Buffalo, although the Hudson River continued to be important to commerce.

The renowned case of People v. Croswell began in Hudson when Harry Croswell published on September 9, 1802 an attack on Thomas Jefferson in the Federalist paper The Wasp. The state’s Democratic-Republican attorney General Ambrose Spencer indicted Croswell for a seditious libel. The case eventually wound up with Alexander Hamilton defending Crosswell before the New York Supreme court in Albany in 1804. Crosswell lost, apparently due the influence of anti-Federalist Justice Morgan Lewis. However, enough state assemblymen had observed the trial that in 1805 they changed the state law on libel.

During the 19th century, considerable industry was developed in Hudson, and the city became known as a factory town. It attracted new waves of immigrants and migrants to industrial jobs. Wealthy factory owners and merchants built fine houses in the Victorian period. Hudson obtained a new charter in 1895. It reached its peak of population in 1930, with 12,337 residents.

In 1935, to celebrate the sesquicentennial of the city, the United States Mint issued the Hudson Half Dollar. The coin is one of the rarest ever minted by the United States Government, with only 10,008 coins struck. On the front of the coin is an image of Henry Hudson’s ship the Half Moon, and on the reverse is the seal of the city. Local legend has it that coin was minted on the direct order of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to thank the Hudson City Democratic Committee for being the first to endorse him for state senator and governor.

In the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, Hudson became notorious as a center of vice, especially gambling and prostitution. The former Diamond Street is today Columbia Street. At the peak of the vice industry, Hudson boasted more than 50 bars. These rackets were mostly broken up in 1951, after surprise raids of Hudson brothels by New York state troopers under orders from Governor Thomas E. Dewey netted several local policemen, among other customers.”(Wikipedia).

Taken with a Fuji X-E3 and Fuji XC 16-50mm f3.5-5.6 OSS II