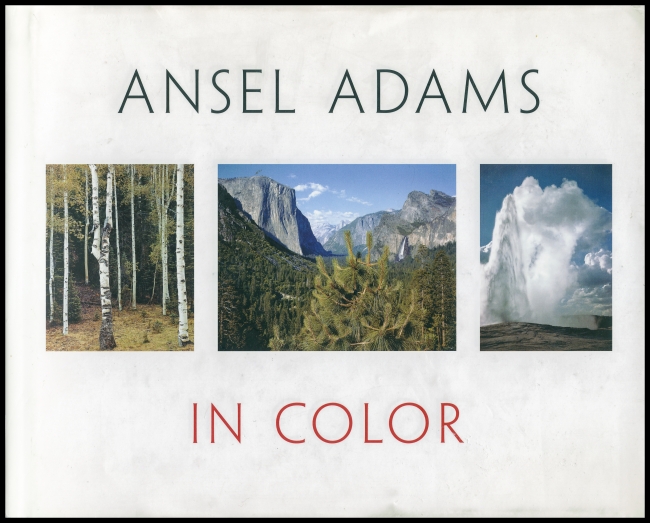

One of this year’s Christmas presents.

Ansel Adams is, of course, best known for his stunning black and white landscapes. But he also shot some color that is the subject of this volume. After a foreword and editor’s note comes an interesting and informative: Introduction: Quest for Color by James L. Enyeart. The bulk of the book is taken up by the Portfolio, consisting of 57 color plates. It concludes with a selection of writings on color photography by Adams himself.

Unfortunately I wasn’t too impressed by the portfolio. The photographs didn’t make me want to look at them more than once.

I think part of the problem is that Adams did not really relate too (or even like very much) color photography.

The introductory essay has him saying:

Color photography is a beguiling siren for the dilettante, but a scourge for the professional and serious photographer. So much is done superficially, so many millions of images are seen, that it is difficult, even for the serious worker, to realize how important are constant observations and visualization, in terms of rigorous practice and experiment.

Another quotation indicates that it bothered him that he didn’t have the control he was used to with black and white photography:

Moved by the scene, I tried to visualize a color photograph. The problem was formidable and I am sorry to say, unmanageable…

I am frustrated by both exposure-scale limitations and rigid film-color response. As “reality” is out of the question, I can indulge myself with explorations of the “unreal” color which may or may not have intriguing aesthetic effects. I would not want “post-card” realism, but I would enjoy “enhancements” of the colors which I fear is not possible with conventional material today…The scope of control with the electronic image has not been explored, but I feel confident astonishing developments await us in this area. (written in 1983).

It’s interesting that in the quotation above he predicts the effects that what we would call digital photography would have especially on color photography.

Towards the end of his life there were signs that he was coming to terms with color (from the introductory essay):

He finally resolved in his own mind that color photography could offer potential aesthetic experiences, it could be seen as a means of simulating reality, rather than recording it.

He came to believe that great aesthetic works, those that exceeded the documentary nature of reality, were possible in color, but that they were due either to the special color sensitivity of unique individuals like Cosindas, Porter and others, or to the careful selection and “seeing” of subjects. He placed himself in the latter category and fought to find a way for other photographers and the audience to unlock the nature of a color aesthetic that could control subject matter, rather than being controlled by it.

However, the quotation below shows that in March, 1984 (Just a month before he died) he was still having problems.

I fear I have become a problem! I don’t like photographic color. I don’t like the print of the Aspens. It is not my dish of tea! Wilder did a wonderful job of exhumation. But the whole idea is of increasing concern to me. While I did an awful lot of color when I was professionalizing, I never got anything that aesthetically pleased me. I know a lot about the mechanics – especially exposure and the application of the Zone System. The visual tests I had a Polaroid show that I have an excellent color perception over the full spectrum. I wish I liked it! Hence, while I have much that is going for color I find it increasingly negative for me. My field is B&W and I should stick to it! From a letter to Mary and Jim Alinder, March 9, 1984.

I suspect that these problems led an inability to fully engage with color photography and resulted in somewhat uninteresting photographs – at least on his terms. If I had taken these pictures I would have been more than pleased.