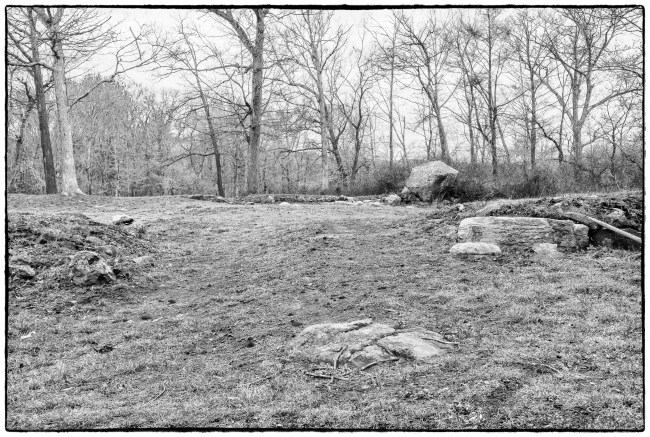

There’s not much to see here nowadays, but this was once the site of the North Redbout.

According to a nearby information board:

Brigadier General George Clinton, the Governor of New York State, commanded Fort Montgomery during the battle of October 6, 1777. Aware the British were approaching, he ordered some of his men to take a 3-pounder cannon down the western road leading to the fort to slow the enemy. The Americans temporarily stopped the 900 advancing British and Loyalist soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Mungo Campbell, but were eventually forced to abandon their gun and return to the fort.

Governor Clinton ordered his undermanned garrison into the fort’s three redoubts, or strong points. British skirmishers approached keeping up a constant fire. After being driven back, the British sent a flag to the fort seeking the Americans’ surrender. When the Americans refused, the British resumed the battle and after several attacks, finally drove the Americans from the redoubts.

As Governor Clinton was rallying his men to continue the fight, a roaring cheer went up from Fort Clinton, proclaiming its capture by the British. Governor Clinton and more than half of the Americans escaped from Fort Montgomery, taking advantage of the battle’s haze and the growing darkness. By nightfall, the British controlled both forts and the Battle of Fort Montgomery was over. All subsequent testimonies by the officers agreed that the soldiers had fought bravely, but that there had not been enough men to defend the forts adequately.

…

The term redoubt at Fort Montgomery means a strong point in the fort’s walls. There were three redoubts at Fort Montgomery, including the North Redoubt, which you see here. Two of the redoubt’s walls projected out from the fort so that enemies approaching the walls of the fort would be exposed to cannon and musket fire from the redoubt. About 15 feet outside the redoubt was a two-foot deep ditch, which would have slowed an approaching enemy.

The lower portions of the redoubt’s walls were formed of earth faced with stones. Assuming the redoubt was built like other sections of the fort, the upper part of the redoubt’s walls were faced with bundles of saplings, called fascines. Around the inside of the redoubt’s walls there was a banquette, or firing step, that soldiers could stand on to fire over the wall. The redoubt probably contained a few 6- or 12-pounder cannons. Archaeologists found evidence of charred wood in the “point” of the redoubt, which was probably the remains of a cannon platform. The presence of pothooks, a fork, bottle glass, ceramics, teapots, and bone scraps suggests that soldiers gathered here to eat and socialize.

According to the Revolutionary War 101 site:

Lt. Col. Mungo Campbell and several British regulars approach the fort with a flag of truce indicating that they wish to avoid `further effusion of blood.’ Clinton sends Lt. Col. William S. Livingston to meet the enemy. The British officer requests that the patriots surrender. They are promised that no harm would come to them. Livingston, in turn, invites Campbell to surrender and promises him and his men good treatment. Fuming at this audacity, the British resume the fight. British ships working against an ebb tide attack the forts and American vessels. A steady volley ensues with each side receiving a share of the bombardment. British officers Campbell and Vaughan close in on all sides of the twin forts. Leading his men into battle, Campbell is killed in a violent attack on the North Redoubt of Fort Montgomery. Vaughan’s horse is shot from under him as he rides into battle at Fort Clinton.

After a fierce battle lasting until dark, the British pushed the courageous Americans from the forts at the points of their bayonets. The defenders are overpowered by sheer numbers and the British gain possession of Forts Montgomery and Clinton. American casualties numbered about 350 killed, wounded and captured, while the British paid a price of at least 190 killed and wounded. Those who were not killed or did not escape are shipped to the infamous Sugar House Prisons in New York City and then onto British “hell ships” (prison ships) in the harbor. A “return,” or report of prisoners, is sent to communities in the Highlands to inform families of their loved ones’ capture. It is up to the families to send provisions lest the prisoners starve. Countless patriots perish on the prison ships.