Alfred Stieglitz was a hugely influential figure in the early history of photography in the the United States. He was married to the famous artist Georgia O’Keeffe and after his death in 1946 she bequeathed their large collection of photographs, paintings and sculptures to a variety of institutions throughout the US, one of which was the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC). The AIC in 1949 received around 400 works from the collection including 244 photographs (159 of which were by Stieglitz).

In 2016 the AIC embarked upon a project to digitize these works. In addition to the photographs themselves they also included an analysis of each of them. Different views (e.g. recto and verso) are provided along with references to other collections. This resulted in the Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

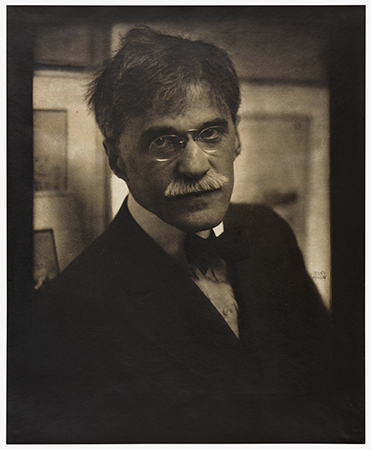

The site is very well presented and easy to use. The collection can be accessed by artist (15 artists are presented including Ansel Adams, J. Craig Annan, Julia Margaret-Cameron, F. Holland Day, Frank Eugene, Frederick H. Evans, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Gertrude Kasebier, Heinrich Kuhn, Eliot Porter, Sarah Choate Sears, Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, Clarence H. White); by photographic process; by gallery; by journal (camera notes; camera work); Stieglitz series (early negative/later print; early work; equivalents; lake george; late work; new york views; portraits of americans; portraits of georgia o’keefe; portraits of rebecca strand); and themes (materials research, nineteenth century; the photo-secession; pictorialism; portraits of stieglitz; print variations; straight photography).

I’ve always been fond of autochromes and I particularly liked this one:

Kitty Stieglitz in a Field with Blue Flowers, 1907. Attributed to Frank Eugene (American, 1865–1936)

A lengthy ‘About’ page provides further information:

On December 9, 1949, the Art Institute of Chicago’s director, Daniel Catton Rich, wrote to his friend Georgia O’Keeffe, the well-known painter and widow of Alfred Stieglitz: “I am happy to inform you that the Trustees of the Art Institute at their recent meeting in November, accepted with great appreciation your splendid gift of paintings, sculpture, drawings, etchings, prints and photographs, to the Alfred Stieglitz Collection.”[1] Including later additions by O’Keeffe, the gift would ultimately total nearly four hundred works, including 244 photographs, 159 by Stieglitz himself. It added enormously to the museum’s holdings of modern American art and utterly transformed the collection of photographs.

Considered as a whole, the Stieglitz Collection reflects the enormous diversity of Alfred Stieglitz’s activities. Through his own dedicated photographic work over the course of a half century, the journals he edited and published (such as Camera Notes and Camera Work), and the groundbreaking exhibitions he organized at his New York galleries (including 291, the Intimate Gallery, and An American Place), Stieglitz tirelessly promoted photography as a fine art, gathering around him first Pictorialist and then modernist photographers. He was unmatched both in his advocacy of modern European painters and sculptors—including Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Auguste Rodin—and in his support of emerging contemporary American artists such as Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Georgia O’Keeffe. The variety of his interests was on full display in his publications and exhibitions, where photography could be found alongside historical precursors and modern contemporaries in other media.

Stieglitz’s vast collection had already begun to fragment during his own lifetime. He donated twenty-seven of his own prints to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1924, followed by twenty-two photographs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1928, both gifts representing the first photographs to be accepted into either museum’s collection. However, he was ambivalent about what to do with his ever-expanding collection of work by other artists—a disordered assemblage gathered over the decades, including gifts and purchases from artists he showed at his galleries as well as works bought from other exhibitions, such as the Armory Show of 1913. As O’Keeffe put it, “He always grumbled about the Collection, not knowing what to do with it, not really wanting it, but in spite of the grumbling it kept growing until the last few years of his life.”[2] In 1933, Stieglitz had been on the verge of destroying a portion of the collection, over four hundred priceless photographic prints by his colleagues and peers, the storage fees for which had become a financial burden; instead, he was convinced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to deposit them there.[3] As he grew older, Stieglitz anticipated the difficulties that future stewards of his collection would face. He told an interviewer in 1937: “I am nearly seventy-four. [W]hat is going to happen to all this if I should die tonight? There is not an institution in this country prepared to take this collection. . . . Broken up, these individual items would be interesting and valuable. But together they are more than that. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”[4]

When Stieglitz died in 1946, O’Keeffe immediately embarked on a major project to reshape and disperse the collection, assisted by Doris Bry and in consultation with Daniel Catton Rich and the curators James Johnson Sweeney and Alfred Barr of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. O’Keeffe’s decision to divide the works among public institutions was a pragmatic one, given the size of the collection. It also represented her commitment to the transmission of Stieglitz’s ideas to the widest possible audience. As she wrote, “It is impossible for me to give the Collection to any one institution and expect his ideas to be housed. The Collection ha[s] grown too large. . . . If the material is not being seen, opinion is not being formed. Having in mind that pictures should be hung, I had to divide it, as I always told him.”[5]

The task of pairing works with their respective destinations proved to be arduous, as O’Keeffe described in a 1948 letter to Rich:

It is baffling—too many things to decide. —I have been working quite steadily on the photographs. I had thought it would take about two weeks. . . . I’ve been at it about a month instead . . . I didn’t intend to have so many groups of photographs but the prints are there—it is difficult to think of selling them—I cannot keep them—they seem too good to destroy—I will be glad when it is finished.[6]

In 1949, O’Keeffe donated representative groups of works to a number of institutions including the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and several others (a complete list is below). Between 1950 and 1952, further gifts were allotted to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the George Eastman House. During this time the Art Institute’s group was enhanced with the addition of a group of autochromes. O’Keeffe chose the Art Institute as one of the recipient museums because of “its central location in our country,” but her personal connections to the museum played a role as well: she was close with Rich and his family, and she had studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.[7] While Stieglitz’s collection as a whole reveals both his remarkable artistic career as well as his discerning eye, its distribution reflects the arbitration of O’Keeffe, who defined how and where the works would be viewed.

As Stieglitz’s chosen medium, photography comprised a special category of the collection, and the group of photographs donated to the Art Institute was second in size only to the “key set” grouping given to the National Gallery of Art, which consisted of an example of every print Stieglitz had mounted and kept in his possession at the time of his death. Of the original 231 photographs and photogravures given to the Art Institute in 1949, which at the time constituted the entirety of the museum’s photography collection, 151 were by Stieglitz himself, spanning from his early student days in late nineteenth-century Germany to his more experimental period in Lake George in the 1930s. In her 1948 letter to Rich, O’Keeffe described these photographs by Stieglitz as “very handsome.”[8] An additional eighty prints by other artists tell the story of his role as a critical figure in the history of photography. These include prints by nineteenth-century practitioners, such as Julia Margaret Cameron and David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, whom Stieglitz saw as predecessors; those of Pictorialists James Craig Annan, F. Holland Day, Gertrude Käsebier, and Heinrich Kühn, as well as early pictures by Edward Steichen, all of which Stieglitz had championed in the pages of his journal Camera Work; and works by Paul Strand and Ansel Adams, younger modernist photographers whom Stieglitz had mentored.

While in 1949 O’Keeffe could not have foreseen the possibilities offered by digitization, the Art Institute of Chicago’s The Alfred Stieglitz Collection: Photographs supports her intention to make the works available to as wide an audience as possible. The site also demonstrates the unique qualities of the prints in the collection of the Art Institute in particular and situates them in the larger context of Stieglitz’s sphere of influence. It is the hope of the authors that the platform introduces new pathways of understanding this seminal group of works, which was shaped as much by O’Keeffe’s foresight as by Stieglitz’s acumen as a collector.

—Jennifer R. Cohen

Andrew W. Mellon Chicago Object Study Initiative (COSI) Research Fellow, 2014–15